Mastering Power Dynamics: The Secret Behind Galileo's Success

Power is a fascinating thing. It's beautiful from far and chaotic from close. The chaos, however, is often not easily noticeable. Why? Well...we are habituated not to notice it. Every decision we make is influenced by one or the other form of power, be it financial power, soft power or even direct orders. Things always influence us, and we can't seriously grow unless we recognise and start playing the game ourselves.

So, how do we play the game? You can dive deeper into the pool blindfolded (or) strat by preparing your arsenal first. You can only prepare your arsenal of tools by analysing things that have already happened. You start looking at them, dissect them, and digest them. Robert Greene had done a fantastic job on this topic in his book, "The 48 Laws of Power".

In today's discussion, we will dive deep into an example of The First Law of Power from the same book. We start with the law and how it was described in the book before slowly diving deeper into the intricacies behind the seemingly straightforward example. I hope you're as excited and intrigued as I am to do that!

Table of Contents

- The First Law

- Greene's version of the story

- The history before the incident.

- The true version of Galileo before 1610

- The Medici before 1610

- Florence around 1610

- The Discovery and its cosmetics.

- What does this change?

- Conclusion

Seems straightforward, isn't it? Well, I thought the same until I started digging. Luckily, you don't have to do the same. So, I hope you'll clap for this article if you appreciate the effort. Of course, responding when needed is even more appreciated!

The First Law

The first law is fairly straightforward, "Never Outshine the Master". Its effects are also straightforward. You don't outshine your master and become a target of insecurity. Rather, play your game while seemingly making your master shine. And the law makes sense.

To help us understand the law even better, the author has given us many examples throughout the book. Today, we're looking at the story presented as an observation of this law, the story of Galileo Galilei becoming the court mathematician for the Medici family.

Greene's version of the story

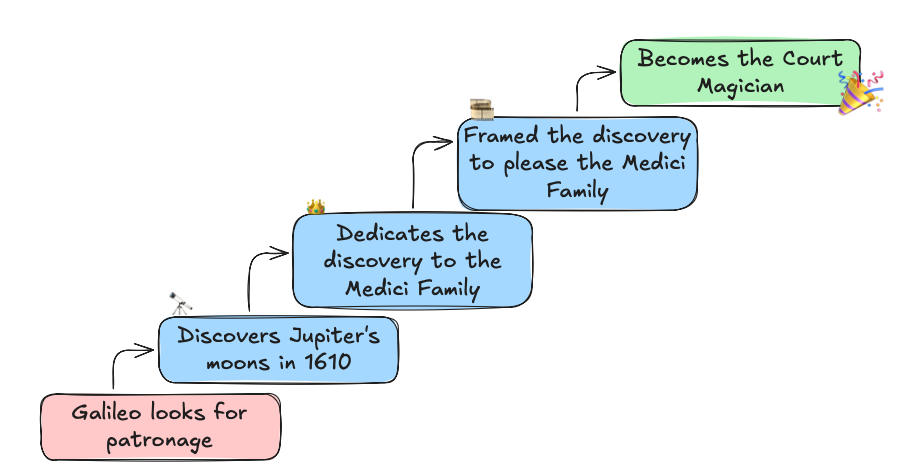

In the book, we see a fairly straightforward story presented. The following image shows the flow of events:

It makes complete sense, doesn't it? But the problem starts when you look at what is missing from this. Is the Medici family so generous that a random scientist offers them a simple tribute, and they add him into their court? Are all the scientists treated the same way? Why are they even bothered with science when they should focus on ruling Tuscany?

To better understand this situation, we must look at each party involved during this incident, mainly Galileo Galilei and Cosimo II de' Medici. So, let's do that as soon as possible.

The world before the incident

So, we start our dive with two questions,

- Who was Galileo before the incident in 1610?

- Who was Cosimo II de' Medici before the incident in 1610?

Following these questions, we branch out into different regions of 17th-century Italy and key figures like Guidabaldo Del Monte, Francesco Del Monte, Ferdinando I de Medici, and many others.

Galileo before 1610

Skipping the childhood arc of the scientist, all we know is that he was one of the three kids (out of five) who had survived infancy and had a younger brother, Michelangelo Galilei, who added to his financial troubles (post-1591 after the death of their father), pushing Galileo to develop inventions that would bring him additional income.

Though Galileo had his ambitions, he was a well-known academician before gaining patronage from the Medici family. He had worked as a professor in Mathematics for reputable universities, published a few books, cultivated the support of many reputable mathematicians and was fairly known as someone who often challenged the established norms.

However, unlike today, the reputable position of a professor didn't guarantee long-term financial stability in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Amplifying this headache was that mathematics was often considered a subordinate of philosophy. This restricted his ability to pursue broader intellectual ambitions, making him look for additional income and patronage.

In the same trail, he had written a letter to Fernandino I de' Medici, requesting an opportunity to tutor the young Cosimo II de' Medici in Mathematics. Fernandino considered the position and helped Galileo establish his initial connection with the Medici family.

All in all, before 1610, Galileo Galilei was a well-known academician with a reputation for challenging the norms and good connections with people. All he wanted was the financial security of his position and support for his scientific endeavours.

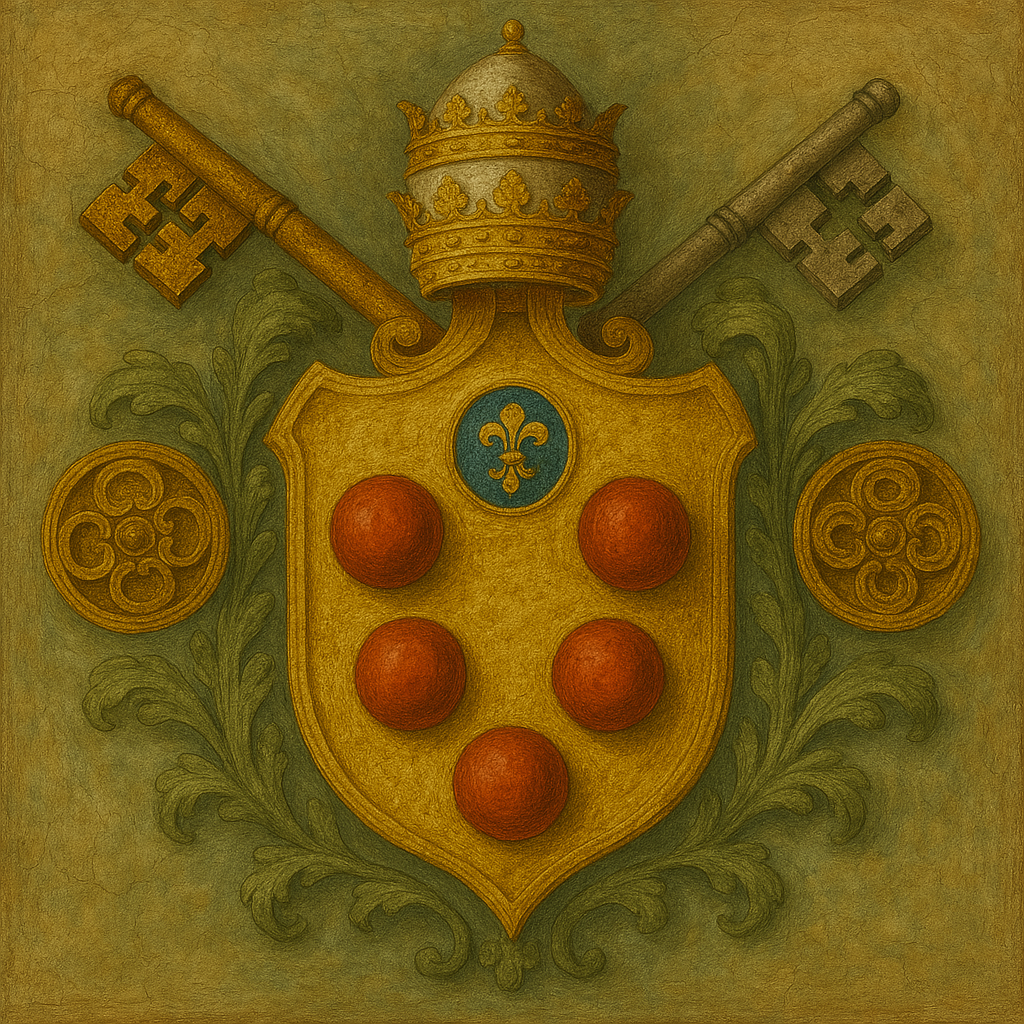

The Medici Family before 1610

We're now going to focus on two people from the Medici house. One is Fernandino I de' Medici, and the other is a young Cosimo II de' Medici. By the end of the 16th century, the Medici family had established a tradition of intellectual curiosity. This inherent curiosity was combined with Fernandino I's understanding of science's potential value and the evolving landscape of his time. This made Fernandino I have a strong inclination towards "modern science". This inclination is specifically noted for his commitment to providing his son and heir, Cosimo, with a modern education.

Cosimo II was often described as "scientifically curious". While his father undoubtedly shaped his education, Cosimo's intellectual curiosity likely made him a more receptive student to subjects like mathematics. Before Fernandino I's death in 1609, Cosimo II's close circle would be limited to his parents, wife, and tutors. Galileo became a part of this circle because of his self-initiative letter to Fernandino, which is said to have established a personal connection between Cosimo II and the Medicis.

Florence around 1610

During the early 17th century, Florence was under the stable rule of the Medici family. The court as a whole had a demonstratable interest in innovations and attracting intellectuals to increase prestige. Despite Cosimo II's young age, the efficient bureaucracy established by Cosimo I was running smoothly, allowing him a degree of detachment from the daily administration.

On the other hand, the Universities across Florence tended to be conservative. This limited the scope for academicians, especially mathematicians, to engage in natural philosophy and gain higher intellectual status within the university system. However, the broader academic community in Europe was experiencing a period of intellectual ferment, with a growing interest in astronomical ideas.

However, conducting scientific research was not without its risks. The Inquisition had previously closed scientific academies under suspicion, indicating a climate where new ideas, particularly those challenging established doctrines, could face opposition.

How did these vastly varying ambitions connect to discovering moons around Jupiter? Did Galileo intend to discover the moons around Jupiter at any cost? Or was it just his luck that the moons he identified were located around Jupiter? It's time to answer these questions.

The Discovery and its cosmetics

In 1609-1610, Galileo was still pursuing his ambition of getting patronage from someone. He wanted financial stability, freedom from teaching duties, a better platform and a return to his native Tuscany. To achieve this, he pursued his telescopic discoveries until Jan 1610, when he discovered Jupiter's moons. Once discovered, he published his findings by March 1610, dedicating it to Cosimo II.

This rushed approach suggests a sense of urgency to capitalise on this discovery. Especially because Jupiter held significant importance to the Medici family, stemming from the reign of Cosimo I. Jupiter was important because it represented the king of Roman gods as a dynastic emblem. Since then, the Medici actively incorporated Jupiter into their artistic and architectural programs.

Along with the importance came the timing of Cosimo II's ascension. Belisario Vinta mainly suggested the discovery's significance and its cosmetic changes. For decades, Belisario was a cornerstone of the Medici administration, and he recognised the potential "political currency" Galileo's discovery could have. He guided Galileo's strategic presentation of his discoveries, particularly the naming of the Medicean Stars. He effectively translated Galileo's scientific achievement into the language of power and dynastic symbolism that resonated most powerfully with the Grand Duke and his influential advisors.

What does this change?

Well, it changes the lens through which we look at Galileo's patronage. Unlike the earlier fully strategic view, we have come to understand that most of Galileo's success relied on luck and timing. Consider the following scenarios,

- If he had seen the moon on a different planet than Jupiter

- If Belisario Vinta was slightly sceptical about the political impacts

- If Guidibaldo Del Monte hadn't asked his brother, Francesco, to recommend Galileo to become a professor

- If Fernandino hadn't considered Galileo's letter requesting a job

- If Cosimo II had been entirely uninterested in science or held his former tutor in less regard.

Galileo's discovery wouldn't have landed him the patronage of the Medici family in any of these highly probable cases. Of course, Galileo's success in securing Medici patronage was not solely a result of luck but rather a masterful blend of strategic action, scientific brilliance, and the fortunate alignment of things that happened at a certain point.

What does this say about the first law of power?

Well, the First Law of Power doesn't seem inapplicable in real life. Instead, Galileo's success suggests that its effective implementation often lies in indirect strategies that focus on enhancing the perceived brilliance and power of the master. Galileo's chance to frame everything in his/ the Medici's favour was very low, but the moment he got the chance, he didn't simply capitalise on an opportunity; he masterfully shaped that opportunity to make his potential patrons shine more brilliantly.

Considering the events surrounding Galileo and the Medici, the First Law appears to be highly applicable, but its application in real life, as demonstrated by Galileo, is often indirect and requires strategic brilliance rather than overt subservience. This often occurs due to scenarios having a very small window of opportunity.

Of course, I tried to compress this discussion as much as possible. I excluded the involvement of key figures in court who held significant power and their interactions with Galileo and Guidabaldo Del Monte, who helped Galileo through his brother, Francesco Del Monte, to be offered positions at universities, etc. However, the discussion covers the crux of the matter fairly straightforwardly.

I hope you have found some value in this article. If you enjoy more such discussions, please follow and stay tuned!

Thank you for reading till the end!