How You Can Make or Break Habits.

On What I Read — Log #3 | Atomic Habits by James Clear

I’ve always enjoyed writing. But something or another always led me to drop it. The same almost happened for this account, as after 17–18 articles, I lost the motivation to keep writing. I always had this nagging feeling that I was not writing an article, but things seemed daunting.

I hid away from the feeling and continued writing an article once or twice a month. But now, things are different. I decided to write daily. What will I write? About the things I read.

In the discussion of habits till now, the author has shared what’s “atomic” about a habit and why identity matters for building or breaking a habit. These things taught me a lot, not because of the sheer knowledge they provided but because of the simple things I always missed. These things made sense and were easily acceptable. However, in Chapter 3, things are different.

We start to look into how we can build the habits and what we can do to integrate them into our lives. But to do that, we must understand how a habit forms or breaks.

So…What’s a habit?

In the first chapter, we’ve discussed that habit is something we do involuntarily. It happens in our subconscious. Here, we dive deeper into why this happens. To summarise everything, Habits are our actions to solve a problem. But there’s a bit more to it.

We have been brushing our teeth since childhood and can confidently call it a habit. But what problem is brushing solving? Keeping our mouth clean? But when we made that a habit, we honestly didn’t care if our mouths were clean. Yet, we have made it a habit by imitating our parents or following their instructions. But still, we have formed a habit, and every time we wake up in the morning, the first thing we want to do is brush our teeth.

From this, I can infer that the “problem-solving” part of the habit is considered important solely in the habit-forming stage, and whether the problem exists or not, the habit keeps happening. And that’s a very important note to keep in mind. If we don’t question our habits, they keep happening without our notice.

Breakdown of making habits.

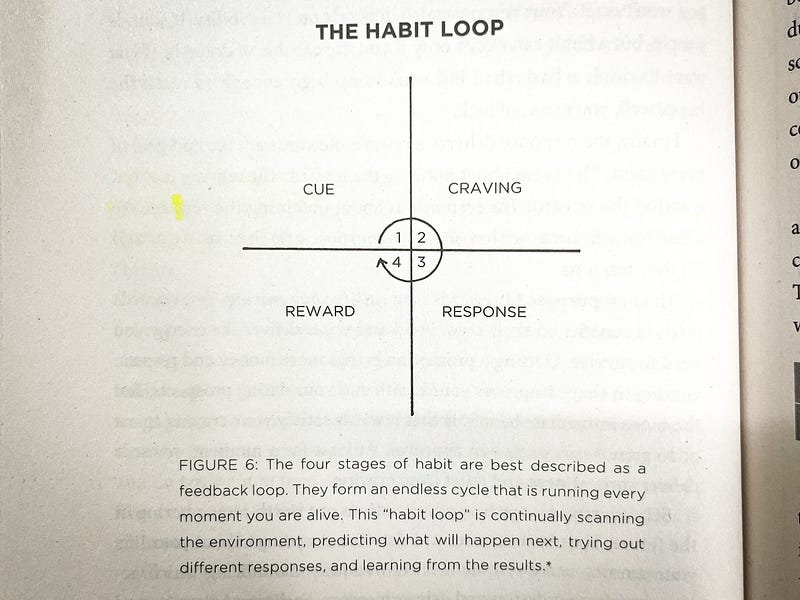

So, now that we have cleared that off, let’s return to making habits. It is said that every habit has a trigger to kick it in.

Room is dark? Turn on the light. The sky is dark? Go to bed. Feeling Hungry? Eat something. So, for every habit, there must be something triggering it. And that’s the important part. We do something when things trigger us to do it.

Now, what happens immediately after we get a trigger? Like, what happens when your body indicates that it needs energy? You search for something to eat. What happens when your teeth feel uncomfortable? You get the urge to clean them. This part is referred to as “craving”.

And what do we do when we have a craving? We respond with an action. Cleaning your teeth, eating food, and going to bed are a few responses to cravings. And why do we respond? What do we get from that? We feel satiated when we eat, energised when we sleep at the right time, and feel our mouths clean when we brush. All of these are rewards that we get for responding to our cravings.

I’m no psychologist expert, but a simple pattern emerges whenever we analyse a habit, Cue-Craving-Response-Reward. That’s what the author shares about habits. Now, it’s in our hands to use this 4-step dissection of a habit to make new ones or break old ones.

How to use this framework?

Let me discuss that with a problem I had: Eating junk food.

The cue for this is simple: hunger. But the craving is slightly complicated: tasty food. What do I look for when I want tasty food? I responded by searching for something that can be done quickly and is tasty, which is mostly junk food. What happens as a result? My hunger is satisfied while my taste buds are happy.

Remember, the key term in the above example is “quickly”. That’s what pushed me into junk food. It’s tasty, and the response is far simpler than cooking a complex dish. Hence, the habit of eating junk food has formed.

What should I do to drop it? Can I change the cue?

No. Hunger is a natural phenomenon. I can’t control it and ask it to come back later. I have to look into the other three issues. But the reward, too, is not in my hands. I want to be satiated; that can’t be changed. I can’t eat food and feel high!

So, the game is now focused on two things: Response and Craving. There’s no need to make junk food more appealing; look at how many insects are acceptable to the FDA when making chocolates. Now look into how many instant foods have similar conditions. The more you eat, the more insects you consume. Heck, even instant coffee has a percentage of insects that can be acceptable! So, the craving is now unappealing.

But what about the response?

I must find a simpler or comparable response to replace junk food. Now, that’s the hard part, and I have to personalise and figure it out.

Well, for that, we have an entire book discussing into making or breaking habits! So, I’ll continue reading it and try to break this habit. What is one habit that you’re trying to break? Share the cue-craving-response breakdown with others in the comments, and let’s discuss!

I hope you found something of value in this article! Thanks for reading till the end. Until next time–happy reading! ✌️